Over the last year, the Schuman roundabout, at the foot of the community institutions in Brussels, has been transformed into a depressing urban shambles. In a decor worthy of an industrial park in a hard boiled crime thriller, cranes, concrete mixers, and scaffolding have taken possession of the administrative and political epicentre of the European Union.

Delays already announced to the works, scheduled to continue until 2014, are a cruel symbol of the decline in the fortunes of the eurocrats who reign over this part of city where the EU’s "founding fathers" — Schuman of course, but also Jean Monnet, Alcide de Gasperi and other less well-known figures such as Emile Noël, general secretary of the Commission from 1967 to 1987 — are venerated. And among such luminaries, one name is repeated more often than all the others: Jacques Delors, the president of the EU executive from 1985 to 1995. On 7 February 1992, with the support of the Kohl-Mitterrand duo, the former French government minister led the eurocracy out of the darkness with the signature of the Maastricht Treaty on monetary union.

Obligation for transparency dragged Commission into abyss

Delors, remembered as a leader who stood his ground against heads of state, charmed the press and embodied the union. Twenty years on, he is still with us. On 7 February, he will be back in Brussels to commemorate Maastricht. But the eurocracy no longer has the same fire of those years. Far from it. Developments that followed 1992 — enlargement to include 15 additional countries by 2007, French and Dutch rejection of the ill-fated European Constitution in 2005, the scramble to adopt the Lisbon Treaty and finally the financial crisis — have been more than enough to douse the flame.

As the EU grew, doubts spread through the 13 stories of Berlaymont, the Commission HQ which today is home from home for 27 Commissioners, one from every country, and their staff. "With the enlargement from 15 countries to 27, we had to integrate 15, 000 new civil servants, of whom a majority were from new member states. You can imagine the shock," remarks a onetime member of the staff of Neil Kinnock, the former British labour leader, who was the European Commissioner in charge of administration in 2004.

Jean Quatremer, Brussel’s correspondent for French daily Libération, argues that the "rupture" came earlier: to be exact in March of 1999, the date of the mass resignation of the Jacques Santer Commission, which had been rocked by scandals surrounding the French Research Commissioner Edith Cresson.

The noughties became the decade in which the obligation for transparency dragged the Commission into the abyss. Competitive entrance examinations as thick as encyclopedias became the norm: careerism was the new orthodoxy. English knocked out French to become the majority language. The system was penetrated by lobbies, and the export of European norms an exalted mission. The single market and competition, raised to the rank of overweening priorities, enthroned the primacy of economics and finance over politics.

The comfortable remuneration enjoyed by European civil servants

In destabilising the euro, the sovereign debt crisis struck at the heart of the administration of the community, which had been made impermeable to criticism by its stubborn esprit de corps. Diana, age 40, a unit head at the European Council, confirms: "The single currency gave us a purpose but it killed our libido," she explains.

Explanation? "By identifying the EU with a currency, the introduction of the euro neglected its values," adds writer Petros Markaris, another Greek who is an adept of the Belgian capital. "the emphasis on finance killed the comprehension of cultural diversity. We abandoned the dream which was the only real community catalyst."

Today this situation has been compounded by personal complications prompted by the crisis. Diana has become a whipping boy for her family in Athens who are eager to vent their spleen over the "givers of orders" in Brussels.

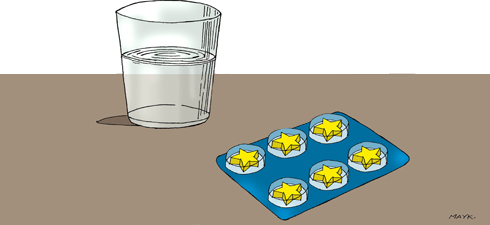

The poison? The comfortable remuneration enjoyed by European civil servants – a minimum gross salary of 3500 euros at entry level, and approximately 18,000 euros for ranked officials reaching the end of their career – taxes capped at a very attractive rate (and returned to the EU budget), scandalous offers of early retirement at age 50 with up to 8,000 euros per month, the privileged world of European schools reserved for their children, in Brussels or in Luxembourg… All the characteristics of an overprotected elite that is impervious to the convulsions of the markets.

Now another hurricane is threatening to fan the flames: the rise of populism and nationalism. Scrutinised, envied, and vilified by the press, European civil servants have become scapegoats, and they cannot even count on their former colleagues to defend them.

"Today the lady is worn out and in bad shape”

Hypocrisy, complain the wounded bureaucrats, is the new order of the day in national governments. Paris lambastes the salaries in Brussels, while fighting tooth and nail to keep the seat of the European parliament in Strasbourg. Luxembourg jealously guards the European Court of Justice where the pay scales are quite simply unparalleled. Member states are battling to become the location for community "agencies" whose numbers have grown from 2 to 36 since 1992.

"The crisis has raised the crucial question of our legitimacy,” admits a Commission senior official. In spite of the fact that they speak several languages, many of our colleagues have lost touch with reality in Europe. They are no longer an avant-garde which takes risks, rather they form a nomenklatura, which, like like its counterpart in the heyday of the USSR, is fearful of losing its privileges."

True? Karel Schwarzenberg smiles. The head of Czech diplomacy, who is also a Swiss citizen, was a supporter of the great Václav Havel. He remembers the dismay of the former Czech dissident, an ardent supporter of the Europe of ideas, the day he was confronted with the endless array of grey offices in Brussels. "Do you think it can be a sexy administration, especially when it does not speak your language and has its seat thousands of kilometres from your home?" he asks.

Have the eurocrats fallen victim to the hazards of history? "Those who joined up the 1960s served a fine young woman named Europe, chortles the truculent Habsbourg prince. Today the lady is worn out and in bad shape. And, just like us, she is not 20 years old anymore."

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!