"It's a scam to exchange one's car for the metro, and it's more expensive. In the car you go quickly, with the rising price of metro [fares], it's almost the same and I started using my car so rarely that I've found myself with a flat battery," says Diana Ralha, a communications consultant, summing up the feelings of those who have had to adapt their habits to the crisis because their pocketbooks have been hit.

No one voluntarily chooses to take longer to go to work or to spend time at home preparing lunch for the next day at the office. When one adopts such habits it's exactly because one does not have a choice. But if it is out of necessity that many Portuguese are forced to change their life style, it is also necessity that hones their ingenuity and creativity. And some even find a positive side to the changes forced on them.

Obviously, the most notable changes are in shopping habits, a domain where a small tweak can reap major savings. Mariana Távora, a lawyer, has made two changes in her outings to the supermarket. First of all she stopped going once a month. "When I did that," she explains, "because there was always something missing, I systematically had to go back in the middle of the week and I systematically came out with a few extra things bought on impulse. So now, I go shopping once a week".

The second change made by Mariana, and perhaps the most astonishing one, concerns the time of day chosen to do the food shopping. Lunchtime is "risky," she says. "I avoid going at lunchtime because when I'm hungry, I always buy more – and more sweets," she explains, conscious of the efforts she makes to avoid the "risk" of impulse buying.

Getting to better know the neighbourhood

Ana Oom, a teacher, has for her part, stopped shopping on internet. "Getting delivered at home made me buy in larger quantities. I started going to a smaller supermarket. I go more often but I'm always very careful. I make more rational choices and when I reach the checkout counter, I always know about how much I'm going to spend" she says.

The crisis is disrupting payment method habits. Bank cards, whether debit or revolving credit cards, are used more parsimoniously. Francisca Lourenço has even stopped using hers. "We realised that by spending only money that we actually have, our budget is better managed and better controlled," she says.

Diana Ralha has sacrificed her debit card to the crisis. "I no longer buy anything by card," she explains, "Every other day, I pull out €20 and make them last as long as possible. That allows me to better manage my budget and to resist the temptation of buying whatever trinket comes within the reach of my bank card".

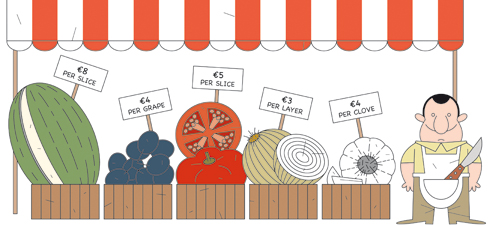

When every cent is counted, store-brand goods and small markets appear as the best asset of those who are tightening their belts. Small stores run by immigrants, are often home to real deals, notes Diana Ralha. "I buy all my fruit and vegetables from the Chinese green grocer on my street who has incredibly low prices," she says. Others want to defend domestic production during the crisis. Mariana Pessoa e Costa only buys Portuguese fruit "to help our farmers. And when there are none, I don't buy any fruit". They all seem to have in common the buying store-brands tactic.

Clothing and transport are two budget lines on which it is difficult, today, for the Portuguese to trim. Many say they recycle clothing. This limits shopping outings and stimulates the creativity of budding fashion designers.

Getting to better know the neighbourhood one has lived in for years and being in better physical shape – these are two of the advantages put forward by those Portuguese forced to walk more often and take public transport in order to save on petrol costs. "It's good physically and, in my case, it allows me to clear my head and to avoid the stress induced by the concentration needed behind the wheel," argues Leonor Tenreiro, a creative writing teacher.

Finding new sources of revenue

But the Portuguese' "new" life does not consist of only savings. The current economic situation seems to have stimulated, in some of them, a taste for risk. Such is the case of Sandra Casanova and her husband who opened a bakery two years ago. "We were born of the crisis and it certainly was a competitive edge for our project," she says.

Inês Custódio also chose to blaze new professional trails. "While this crazy crisis was in full swing, I decided to leave my job to start a business. So that this choice wasn't totally crazy, I had to make even more savings. I managed to sell my house with a small profit, I paid back the credit and now I rent a smaller, cheaper apartment," she explains.

New projects aside, the Portuguese are returning to tried and true methods. On-line sites like OLX and Custo Justo [Right Price] are often mentioned as good ways to improve the family's resources. "I discovered that I could earn a lot of money by selling the children's things and all sorts of objects on internet. I even managed to sell the youngest child's stroller for more than I bought it," says a satisfied Diana Ralha.

The goals set by many Portuguese, whatever the solutions they find in these times of austerity, are finding new sources of revenue and cutting back expenses by adopting new shopping habits. If they do so, it is because they don't have a choice. Those that we met manage, little by little, to elude the crisis because they are not in a desperate situation. But those that see the bright side of these life-syle changes remain rare.

Economy

Fear of the Greek syndrome

According to Portugal’s Observatorio, an anti-poverty initiative, the classic victims of poverty – the long-term unemployed – have in recent months been joined by the “new poor”, reports Público: employees who are being hit by austerity measures, those with precarious or “flexi” jobs, and those who have seen their wages cut.

For its part, the government is still aiming to bring in a balanced budget by 2013 to regain access to the sovereign debt market, and without having to ask further aid from the EU/ECB/IMF troika. It’s a “mission impossible”, notes the Jornal de Negócios, made even more difficult in light of interest on Portuguese two-year bonds hitting 21.6% last week.

“For the markets,” writes Spain’s La Vanguardia, that means “a potentially dangerous equivalence between Greece and Portugal has set in.” According to the Barcelona daily, the hypothesis of an agreement between Athens and its creditors on a partial default is suggesting to the markets that other countries in payment difficulties – starting with Portugal – could soon be facing debt restructuring.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!