Sebastian Müller, a thirty-year-old engineer, had no reason to complain about his job in which he earned over 4,500 euros a month, at the Audi plant in Ingolstadt near Munich. And yet he returned to his native region of Lausitz in eastern Germany to go to work for a small car parts manufacturer. “I earn less, but am happier than I was in the West”, he told Der Spiegel.

As it turns out, Mr Müller is not an exception. Already this year, hundreds of people have returned from western Germany to the former GDR in what the prestigious Institute for Employment Research (IAB) in Nuremberg has described as a trend reversal. Until recently, it was east Germany that was experiencing depopulation, now the tide is turning.

No blooming landscapes

In the summer of 1990, a few weeks before reunification, chancellor Helmut Kohl famously promised to transform the eastern states into ”blooming landscapes”.

But although some 1,500 billion euros were pumped into the region over the following twelve or so years, the blooming landscapes failed to materialise. Industries, which had previously been managed by the state, proved to be uncompetitive, and people suddenly discovered the bitter taste of unemployment.

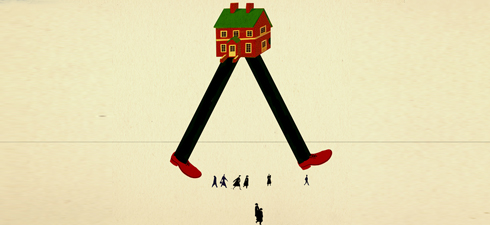

Some 2 million people left the so called “new German states” and headed west to find jobs: in 1990 alone, the state of Saxony on the Polish border saw its population fall by 130,000. The exodus proved to be devastating. The best-educated workers (for example, close to 60% emigrants from Mecklenburg-Vorpommern had university degrees), many of whom were women, flocked to Munich, Düsseldorf and Hamburg, while the former East continued to haemorrhage skilled labour and future parents. The main feature of the former East German towns, as many Germans were wont to point out, was that “only the old people and the NPD neo-Nazis had stayed”.

Change in the former GDR was epitomised by the demolition of communist-style apartment block estates, which no longer had people to live in them (over 130,000 apartments were scrapped in this way), and the closing of schools that had run short of pupils. Buoyed by the brain drain to the western Länder, which had forced many companies to go out of business, unemployment continued to rise. Only a few years ago, most experts forecast that by 2015 the former East Germany would be hit by a serious demographic crisis, but the catastrophe failed to materialise. According to Der Spiegel, last year 3,000 more people returned to Saxony than left it. Brandenburg was also in the black in terms of population growth and Thuringia’s migration balance was at zero.

Saxon, come home!

“Do you feel the nostalgia? Hoist your sails and call in. You won’t regret it!” urges a video commercial on MV4You, a website which takes its name from an acronym for “Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania for you”. MV4You features video clips about a Rostock girl who sought her fortune in Düsseldorf until she decided to return home. But perhaps more importantly, in its bid to attract migration, it also has a long list of job offers. Saxony, in turn, has launched a similar campaign entitled “Saxon, come home!”

Ten years ago, such projects, which at best managed to attract perhaps a few dozen people a year, were viewed with scepticism. Today things have changed and local politicians are joining the effort as well. In early April, Reiner Haseloff, the minister-president of Saxony-Anhalt, went on a tour around the former West Germany in a bid to bring home 5,000 emigrants.

Town mayors have launched similar efforts, and it looks like they may succeed. According to the prestigious IAB institute in Nuremberg, two in three emigrants are now considering going back.

Anti-Ossi discrimination

The Ossis are going home because no one really welcomed them in the West. Considered second-rate citizens and the target of numerous jokes about their communist-era upbringing and their inability to adapt to western customs, many of them complained about living in quasi-ghettos with hardly any contact with the Wessis: a life of “ostalgia” mitigated by shopping for GDR food at special Ossi online shops that mushroomed in response to popular demand.

Sometimes the press still writes about the new Länder as if they were a different country. In 2010, there was a lot of publicity about an East-Berlin accountant who applied for a job in Stuttgart. Her application was rejected and someone wrote “DDR” on her CV. The woman sued claiming she was the victim of ethnic discrimination, but lost on formal grounds because the court decided that there was no such thing as East German ethnicity.

In the former East, no one discriminates against Ossis and – most crucially – jobs are available. The rate of unemployment remains high, often twoce as hight as in the former West — in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, it is close to 15% — but local industries have an urgent need for engineers and IT specialists. Mr Kohl’s vision from twenty years ago has begun to materialise, and by the end of the present decade, the new Länder are expected to have caught up with their rivals in the former West in terms of living standards.

Their renovated townhouses and vibrant universities are already the envy of many cities in western Germany. Dresden, for instance, has become one of Germany’s ten fastest-growing cities, and Jena in Thuringia is now a major centre for high-tech industries.

Wages in the former East are about a third lower than in the West, but rent and food prices are also lower too, so returning Ossis will not have to contend with income shock.

Sociologists add that their experience of mobility, hard work and courage in the West will be a force for change in the East, where it will be of benefit to their new-old neighbours.

But experts remain wary, warning that growth in the former GDR may have weak foundations. Companies there are now doing well because the entire country is prosperous, but that prosperity won’t last forever. Sometime soon, the wave of returning migrants may subside.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!