The European Parliament and the Council finally, on May 29, reached an agreement on a new legislative package on Schengen. A compromise, but better than nothing. The new governance of the area without internal borders got the go-ahead after the process had been blocked for a year and a half because of clashing opinions between Parliament and the Council.

The question, however, is whether the new governance is a step forward or a step back. That, naturally, depends on the side one stands on, but also on the way in which European governments will take the recent compromise.

A brief history: in 1985, in the Luxembourg town of Schengen, seven European Community countries – the EU of the time – signed an agreement to abolish internal borders, which, in practice, they did 10 years later. Many states have since joined the borderless area, including non-member states such as Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and Liechtenstein, and today the Schengen area has 30 members, including 27 which currently use the agreement, while the others are completing transition formalities.

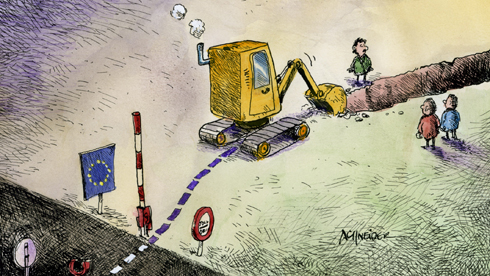

Everything was going well until, in recent years, massive numbers of immigrants began to be troublesome for some of the national populations, and politicians could not remain indifferent to that. The situation worsened with the economic crisis, and as a result, it became urgent to introduce new rules in the Schengen area.

Meanwhile, some member states unilaterally decided to suspend the agreement – for example France and Italy, in the spring of 2011, citing the pressure of thousands of North African immigrants. Or Denmark the same year, for rather electoral reasons: to win a few votes before the fall elections. Despite the playup of the suspension of the agreement in the media, the centre-right government nonetheless lost the elections. Naturally, neither France, nor Italy nor Denmark were sanctioned by the European Commission.

Clash of opinions

The new system of governance of the Schengen area arises from a confrontation between two opposing perspectives – those of the governments (the Council), which wants more freedom for states to allow them to reinstate border controls whenever they deem it necessary, and those of the European Parliament, which wants to impose strict conditions on the unilateral suspension of the agreement, to defend the right of European citizens to freedom of movement.

The Council and the Parliament finally found a middle ground. The member states will be able to reintroduce border controls for up to two years, whenever they feel threatened by a massive wave of immigration. The formalities for entry into the Schengen area for non-EU citizens (even for those who need no visa) will become stricter. Travellers will have to register online, under the model already applied in the United States. To guard against abuse, the Commission will monitor the implementation of the measures to reintroduce controls. The new governance will enter into force on January 1, 2014.

Romanian MEP Renate Weber [ALDE, Liberals], who led the negotiations over the Schengen Borders Code[1] on behalf of the European Parliament, says that the agreement has the merit of having laid down common rules for the reintroduction of controls, and that only in exceptional circumstances.

In the end, who will decide if a situation is exceptional? Governments, at least at the start. And here is the risk that the decision will not always be based on technical considerations, but on political considerations as well. Threats may be "exaggerated" for electoral reasons, like the clamour over the “Romanian invasion” in the United Kingdom (which, however, is not in the Schengen area) and "the attack of crows" that Swiss opponents of entry into the Schengen area based their campaign on.

‘Almost ungovernable country’

This spring, the German Association of Cities complained to the federal government that immigrants – Romanians in particular – are imposing a heavy burden on social protection systems and are requiring municipalities to spend too much. Can that be considered an exceptional situation?

In any case, according to Energy Commissioner Günther Oettinger, Romania, together with Bulgaria and Italy, is an "almost ungovernable" country – an exaggerated claim, of course (we can only be a badly governed country). The government in Berlin, however, was in no hurry to distance itself from the statement. And an "almost ungovernable" country engenders – does it not? – regional instability, including a flood of migrants.

All this is, of course, pure speculation. It does, nonetheless, show that the recent compromise on the new mode of functioning of the Schengen area may be a step forward – or a step backwards, at the whim of the governments of the member states, who may or may not act in good faith.

The agreement expressly declares that Romania and the Bulgaria are no longer considered “candidates” for the Schengen area, since they have already reached the required technical acquis (the common set of Schengen rules) and are legally bound to join the area. On the other hand, the new evaluation mechanism no longer refers to criteria such as corruption and organised crime, often invoked by certain countries as a pretext to block the countries’ access to the Schengen area. Their accession could therefore be facilitated following this compromise, and we consider that, with a mechanism that allows controls to be reintroduced, member states will be more relaxed about the two Danube countries.

It also depends, though, on political calculations in the capitals of the member countries of the agreement – and to a lesser extent, if at all, on the Commission or the European Parliament.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!