It’s a reality that for some time now Euroscepticism has been eating away at the European Union. In Britain, Cameron promises a referendum by 2017 on the UK’s membership in the EU. In Italy, Grillo proposes abandoning the euro. In France, Le Pen is also calling for a referendum to dump the euro and get out of the EU. Even countries such as ours, rock-solid Europeans until recently, we have noticed that faith in the benefits of a united Europe is beginning to waver.

It is debatable if this general dissatisfaction concerns the idea of a United Europe or just the way that Europe is coming together, but what is undeniable is that the phenomenon exists, and that it is growing. It is extraordinary: little more than 10 years ago, when we took on the euro and the economic crisis was not even on the horizon, it was an almost unquestioned truth that the EU would be the great power of the 21st Century, and everyone was eager to get into to it; today the opposite is true.

The economic crisis is threatening to liquidate the best political idea we Europeans have ever had in our entire history. It is true that this crisis is not economic (or not only), but above all a political crisis, and it is also true that it did not start out in Europe. Regardless: what is important is that more Europeans are blaming the dire situation on the European Union.

That is, somehow, logical: nothing gives such temporary relief as blaming someone else for one’s own misfortune and, in the same way that we Catalans have discovered how wonderful it is to blame Spain for everything bad (because this way we don't have to take the responsibility for it), Europeans are discovering how wonderful it is to do the same with the European Union.

In view of this scenario, some clear heads are trying to come up with alternatives to the current EU; the most recent to do so (or the second-most recent) has been Giorgio Agamben. In an article published in La Repubblica, Agamben laments that the current EU has been created on a foundation that is purely economic, ignoring cultural kinships.

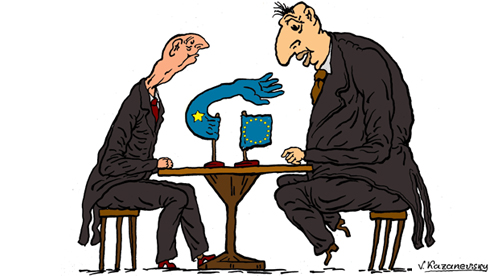

According to him, this option is showing all its fragility today, especially from the economic point of view: the attempted unity has become an accentuation of differences, imposing the interests of a rich minority, which often coincide with those of a single nation (Germany), onto a poor majority.

Defence against greed

Agamben seeks an alternative to this alleged error in an idea expressed in 1947 by Alexander Kojève: the idea of a Latin union, a community led by France that would join politically and economically the three great Latin Nations (France, Italy and Spain), through their way of life, culture and religion. Agamben writes: “Not only is there no sense in asking a Greek or an Italian to live like a German, but even if this were possible, it would lead to the destruction of a cultural heritage that exists as a way of life.”

The diagnosis of Agamben seems to me to be partly successful; his remedy, all wrong. It is true that Germany is imposing an accord on Europe with only its interests in mind, and that accord in the end is unjust. But, on the one hand, I don't see how we can create a poor Europe united by France and a rich Europe united by Germany, especially considering that the major recent troubles in Europe have grown out of the confrontation between France and Germany.

On the other hand, it is absurd to think that poor and fragile Latin Europe could defend itself against the irrational greed of markets and protect its democracy that way, when in fact neither could rich and strong Germanic Europe. It is just as absurd to think that either of the two could single-handedly take on China or India and prevent Europe from being reduced to irrelevance.

Moreover, could the Basques or the Lombards, in this hypothetical Latin Europe, not say that there is no sense in forcing them to live as Spaniards or Italians and lose their cultural heritage? Should not one of the greatest strengths of a united Europe be precisely the achievement of political and economic unity without loss of cultural diversity, without anyone forcing anyone else to live a way of life that he does not want to?

Does there not lurk in Agamben’s argument the main historical enemy of Europe, nationalism? Does there not lurk in the background of the new Europe of Agamben’s argument the old Europe? It’s up to you to decide.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!