A thousand precautions are taken to avoid the inspectors. In Germany, executives at fire truck manufacturers discreetly communicated with prepaid phone cards, separate from their regular subscriptions, just like the urban drug traffickers in cult television series “The Wire”.

In the case of an air cargo cartel, that Brussels fined a hefty €169m last year, executives of major groups (UPS, Panalpina, Kühne & Nagel, Deutsche Post, Deutsche Bahn, etc.) created e-mail addresses on Yahoo to avoid using their companies’ messaging systems. The individual who managed the cartel, evidently a fan of green plants, formed a “gardening club” with his colleagues to chat about “asparagus” and “zucchini”. The name of each vegetable referred, in reality, to a specific surcharge mechanism.

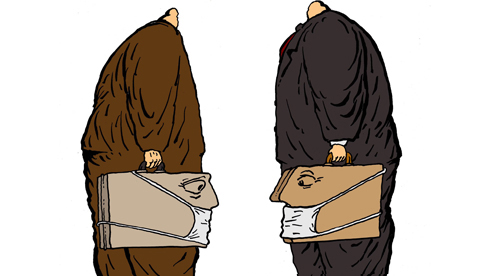

This sophistication explains how cartels can endure for many years. But, in this case as in many others, the gardeners eventually deserted the club, as there always comes the time when one of the members of a cartel whips off the covers. Sometimes whistleblowers of a company involved in the cartel ring up Brussels, and not necessarily for the reasons one might expect. One European official remembers seeing an executive arrive in his office with all the documents compromising his company tucked under his arm. A white knight? Not really. The executive had found a rather practical way to even the score with the cartel’s organiser, who was having an affair with his wife.

Most often, the firms in the cartels end up blowing the whistle themselves. Sometimes the very success of the cartels attracts more and more members, which tends to water down the sense of loyalty. It also happens that when Brussels turns its attention to a related sector, the cartel members start to fear the roving spotlights. The “gardening club”, for example, shared hangars with big air cargo carriers (Air France-KLM, British Airways, Air Canada, etc.), all of which the Commission severely punished for a separate agreement in 2010. “That made some people thoughtful, and no doubt it partly explains why Deutsche Post denounced its fellow green thumbs,” said one expert. The most common reason, though, is much more straightforward: the game is often given up when one of the companies of the cartel is acquired by an outsider. The new owner notices what’s going on and, to keep from getting mired in it, rings up Brussels.

Blowing the whistle must be done quickly, since the members of the cartel often start thinking the same thing at the same time. While members may have worked together for years, the mutual trust is rarely overwhelming, and only the first to approach the Commission enjoys full immunity. That issue of immunity is so important that companies hauled before the EU Court of Justice sometimes contest the “arrival rankings” adopted by the Commission in sorting out who squealed first. Indeed, the difference can run into tens of millions of euros in fines. To assign the ranking in the list of eager collaborators, Brussels does of course take note of the time the company joined in the investigation, but also notes the value of what the company brings to it.

With a “penitent” on board, everything becomes easier for the Commission. Organisation of the cartel, objectives pursued, number of members: these confessions give the Commission a clear overview of the whole picture. Still, before severe punishments are meted out, more evidence has to be gathered: damning documents, suspicious e-mails, the kind of items that cannot be collected without what, in speed and intensity, looks like police raids. European officials arrive in large numbers for surprise inspections, often refuse taking lifts to avoid unfortunate mechanical breakdowns that would leave them stranded for long hours, and search everything from cabinets to computers. SMS left on mobile phones also come under scrutiny. Seals are slapped on. Sometimes the team comes across divorce papers or e-mails from mistresses. More often, though, they find what they came to look for, barring sneaky tricks.

Once, a panicked executive threw all the compromising papers into the toilets. Panic struck when the company lawyers grasped what was happening. The employees of the group eventually had to retrieve the incriminating documents from the water pipes of the building, a little crumpled, but perfectly usable.

All of Europe now knows what to expect: it’s better to work with Brussels than pay the hefty fines. A scan the roster of companies that have denounced a cartel to the Commission over the last ten years reveals a comprehensive list. The sole French company is the former Rhône-Poulenc, which denounced two different cartels in the vitamin trade nearly fifteen years ago. That’s not a lot. In Germany, by contrast, company groups traumatised by the Siemens bribery scandal of ten years ago no longer wait around to blow the whistle.

The Italian groups are not conspicuous in their hurry to come clean in this matter. In 2002, Deltafina did the forbidden and betrayed an agreement to fix prices in the transalpine raw tobacco market. Was it afraid of its own boldness? At the next meeting with the members of the cartel, the group warned the others that it had already lost its nerve – a kind of whistle-blowing forbidden by Brussels. As a result, Deltafina lost its immunity and had to pay a fine like the others. Cultural reflexes die hard.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!