”Nein”. The decision of the Austrian policeman allows for no appeal: ”Die Flüchtlinge bleiben in Italian” [The refugees remain in Italy]. Here, they shall not pass.

Migrants who want to scale Fortress Europe are stonewalled at the Brenner Pass. And ”nein” means ”nein”, period. No point in trying to move the guard to compassion: rules are rules. Schengen or no Schengen. Especially here, at the Brenner Pass, 1,400 metres above sea level. Lampedusa is 1,836 kilometres away, at the other end of the boot of Italy: they have crossed the country in the hope of climbing to the north and getting into Germany or Scandinavia and their legendary welfare states.

There was a time where this border was real. With police officers, Carabinieri, the Guardia di Finanza, and customs officers. Fences, metal gates, surveillance cameras. There were controls, and all vehicles were stopped at the border. A passport was needed. The turning point came in April 1998, when the barriers were lifted for good. Today, if not for some signs, you would even not realise you had crossed into Austria.

Forty thousand vehicles pass though here every day, or 14.6 million every year. Seventy per cent are cars and motorcycles, and heavy trucks make up the remaining 30 per cent. And who stops the migrants crammed into cars (up to six people, not counting the smuggler) or hidden in the trucks? No one, clearly.

Austria the inpenetrable

For those who choose the train, things are different. Very different. [[Austria has become impenetrable, a little like Switzerland. And the constant rejections at the border, with no stirrings of mercy, reveal a Europe that shows little regard for Italy, for its coasts, for “its” migrants]]. But we, at least, do not expel the vulnerable: women, children, the elderly, the disabled.

The legislation drawn up in Vienna lacks these sorts of clauses. Vienna can, however, fall back on a far more important document: the bilateral treaty signed with Italy, under which the illegal immigrant may be ”readmitted to the territory from which he is assumed to have arrived irregularly”. In other words: they’re your problem, you look after them. It’s the same treaty that allows France and Slovenia to turn migrants back at Ventimiglia and Tarvisio, the two other passes over the Alps. The same treaty that Italy applies in turn to return to Tunisian its own migrants.

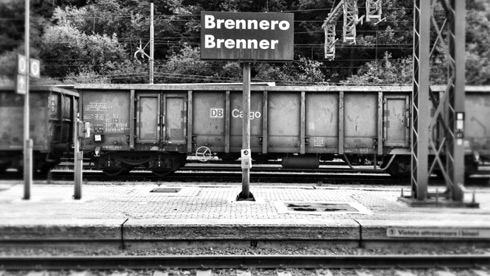

Dozens of convoys pass every day through the small railway station of Brennero. The night is reserved for freight trains: passenger trains are scarce. The Polfer, our railway police, keeps vigil. But above all, it’s the Austrian agents who are on the watch. In recent months, Vienna has sent in battalions of them. The gendarmes patrol the trains, “flush out” whole groups of refugees, take them off the train and escort them back to the border. Treated as postal parcels by the European bureaucracies. Once they travelled hidden among the wagons, under heavy tarps, in refrigerated trucks. Today they are found in the railway stations, with valid tickets.

”We must review the agreements”, says the prefect of Bolzano, Lucio Carluccio. In just three months, Austria has taken 881 migrants back to the border – nearly a thousand people, deported at the Brenner Pass. A quarter of them were minors. Half were Syrians, and others originated mostly from Somalia and Eritrea.

When they are stranded at the border, the tensions worsen, and for good reason. The migrants who do not want to stop in Italy because their destination is Germany or another country carefully avoid being registered by the Italian police: once they have lodged an asylum application with us, they can no longer leave.

They are phantoms destined to pop up somewhere else. In Sweden, perhaps. ”They could start to work immediately there (in Italy, you must wait six months) and be given a good place to stay”, sums up Andrea Tremolada of Volontarius, an NGO that looks after the refugees in Alto Adige.

If you are deported by the Austrians, you are brought to the barracks housed in the Brennero police station, opposite the train station. The police will then have to take your description and you’ll be screwed then, because your fingerprints will end up in Eurodac, the database of the Schengen area. You will become “traceable”, with a name and matching face. Once entered into the files in Italy, you can no longer reappear as if by magic in another country.

Passing on the problem

”Austria and Germany must lend a hand to Italy”, pleads Caritas Italy. On August 30, Austria’s Foreign Minister Michael Spindelegger announced that magnanimous Austria was willing to take in 500 Syrian refugees. Five hundred, handpicked: ”First women, children and Christians”. Really.

[[Driven by despair, illegal immigrants will stop at nothing. And they will come back, as many times as it takes]]. Arrested on the trains, they may try their luck again on foot. Turned away once again, they will turn to a smuggler.

The last was arraigned here on October 3. A taxi driver from Milan was caught at the Vipiteno/Sterzing motorway exit driving a Fiat Ducato van with nine Syrians on board. He said he had charged them €1,300 in total. Rubbish. He said he was acting in good faith. Rubbish. ”He faces three and a half years in prison for smuggling migrants”. Rubbish: a year, a year and a half at most, suspended sentence, and without picking up a criminal record.

The game is worth it. Especially if you drive a rental car. This way, if things go wrong, you avoid having your own car confiscated. Or if you are part of the network that helps the refugees, mostly Afghans, to move on without leaving any traces behind them. A functionary lets out the blunt truth, which he conceals with cynicism. All the while watching you from the corner of the eye, his voice drops softly: ”From time to time, sure we stop a few smugglers, but why go to the trouble? After all, we should be thanking them instead: they get rid of some of the migrants for us.”

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!